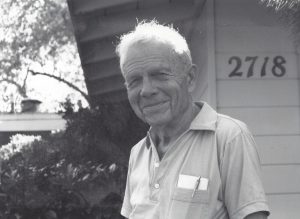

Palo Alto, California was probably about the best place Dwight and Louise could have selected for their retirement. Having lived there previously during Dwight’s time as a Fellow at the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences from 1969-1970, they were quite familiar with the area. The weather was mild–no more Massachusetts winters–and there was only one step up into the single-level Palo Alto house, unlike the multi-level Belmont house which was hard on Louise’s knees. Stanford University appointed Dwight as a Visiting Professor Emeritus of Linguistics, which led to his serving as an adviser for linguistics graduate students, and which meant that he had free use of Stanford Library. He also could take advantage of the shuttle between the Stanford and U.C. Berkeley campuses. And it was the Stanford Library, Special Collections, to which Dwight would leave his papers after he died. Family connections were also a consideration in selecting Palo Alto. Their son, Bruce, and Louise’s two sisters, Mimi and Malvina, and their families lived in California. Dwight and Louise quickly made friends with their neighbors on Ramona St. There was a Co-op market close by and the streets were perfect for bicycling, Dwight’s favorite exercise.

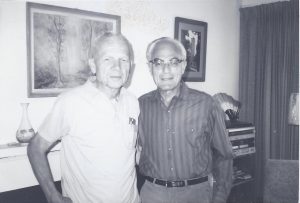

Professional colleagues of Dwight living in California or passing through San Francisco could conveniently pay them a visit.

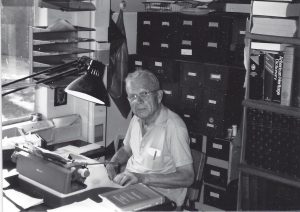

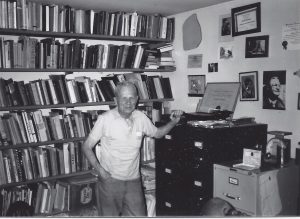

The house even had a spare bedroom which Dwight turned into a study, unlike Los Angeles where he had to use the garage and Belmont where he was in the attic.

Another benefit was the convenient access to Stanford University Press, which published Joseph Greenberg’s Universals of Human Language in 1978 which included Dwight’s contribution, “Intonation and Its Uses,” (number 252 in the full bibliography on this website). Stanford University Press went on to publish Dwight’s last two books, Intonation and Its Parts: Melody in Spoken English in 1986 (number 298) and Intonation and Its Uses: Melody in Grammar and Discourse in 1989 (number 316). Speaking of his Intonation and Its Uses, Dwight said of this scholarly output, it is “my last symphony.” (By the end of August, 2017, Stanford University Press reported that sales amounted to almost 3,000 copies for the two books combined.)

Dwight’s years in Palo Alto were marked by occasional talks to linguists and language teachers in the Bay Area. In October 1982 he addressed the meeting of the California Association of Teachers of English to Speakers of Other Languages (CATESOL) (see below for a reproduction of his remarks) and in 1987 he gave a talk, “Power to the Utterance,” to the Berkeley Linguistics Society. (A sound file and a pdf file of the latter appear on another page of this website.)

In spite of being retired, Dwight’s continuing involvement in the linguistics profession led to his being elected president (1975-76) of the Linguistic Association of Canada and the United States (LACUS). The history of LACUS describes its founding as follows:

“LACUS was founded in August 1974 by a group of linguists of the Great Lakes Region. Their plan was to create a forum for the free flow of ideas and discussion on human communicating behavior from all possible points of view, going beyond traditional grammatical studies in the various tradtional modes.

“Their thinking was in part influence by an enjoyable informal meeting held the year earlier, in the summer of 1973 in Seattle. It was a time of lively argumentation and occasional intolerance at meetings of established linguistics organizations.

“As the inaugural meeting of 1974 at Lake Forest College drew to a close, it seemed clear from the reactions of those present that many linguists from around the world would respond positively to such an organization.

“It was decided to hold an annual Forum at a university campus each year, alternating between Canada and the United States. The 1975 meeting was at the University of Toronto. The 1976 Meeting was at the University of Texas at El Paso, and the first elected President, Professor Dwight L. Bolinger of Harvard University, delivered the first Presidential Address in Ciudad Juarez on the Mexican side of the border.”

Honors came aplenty during retirement. Fellow, American Academy of Arts and Sciences (1973); Orwell Award, National Council of Teachers of English (1981); Corresponding Member, Royal Spanish Academy (1988); Corresponding Fellow, British Academy (1990).

During his retirement in Palo Alto, Dwight had an impact on California politics and election law. The California State Supreme Court had declared unconstitutional the provision of law determining the order of the names of candidates on the ballot–incumbents first with everyone else in alphabetical order. His son, Bruce, was then working for the California Legislature on election law reform. There was a need to establish a new rule on ballot order of candidates’ names but the Legislature had been unable to agree on what it should be. Bruce discussed this with Dwight who came up with a simple solution: have a drawing of the letters of the alphabet at each election to create a random alphabet which would be used to determine the order of the candidates’ names in all election contests. The Legislature enacted the new law. For a more details, see the following pdf file: Something New in Ballot Alphabets, Sacramento Bee, Oct. 19, 1975.

During their years in Palo Alto, Dwight and Louise had the opportunity for some travel, including Spain, Peru (1973), and Austria (1977).

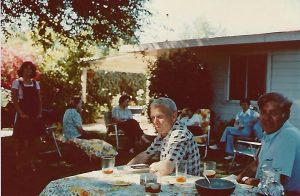

In 1980, Dwight and Louise’s son Bruce married the former Charlotte Brux McKinney. Bruce and Charlotte moved to Nevada City, north of Sacramento, where he went to work for Nevada County. Dwight and Louise would make trips from Palo Alto to the picturesque Gold Rush town of Nevada City to visit them.

Robert Stockwell, in his obituary of Dwight for Language, wrote of Louise’s role in Dwight’s career: ” She also was the critic to whom Dwight submitted every word before anyone else saw it; she commented extensively, and did much of the final typing for him.” (Their daughter, Ann, thinks this might be a bit of an overstatement, at least as far as technical material was concerned. Bruce can recall discussions between Dwight and Louise about how best he should word some other things, such as correspondence and recommendations.) Because she was fluent in French, she could also translate articles on linguistics from French to English. She spoke Spanish, which helped with his professional relations with colleagues from Spain and Latin America, and, of course, conducted all the social duties expected of a university professor’s wife. In 1943, when Dwight applied for a Sterling Fellowship at Yale, he headed for the Topeka Post Office on his bicycle, carrying the application with him to mail, but lost it on the way. Thinking that he did not really have any chance of being awarded the fellowship, Dwight was ready to forget the whole matter and not bother to make out a new application. It was Louise who retraced every inch of his route, found the application where it had fallen out of his pocket, and mailed it. The Sterling Fellowship was followed by his appointment to U.S.C. Dwight’s professional success was certainly, in large part, the result of the support he had from Louise. Her death in 1986 was a great blow to him.