In the summer of 1933, Dwight drove to Phoenix and from there to Cañon, Arizona where his Aunt Grace and Uncle John Albins were now living. He spent six weeks visiting them and their sons. With the temperature reaching 110 degrees in the shade, he was open to the offer of a poster advertising a $5 round trip bus ticket from Phoenix to Los Angeles. Never having even seen the Pacific Ocean, L.A., or California, and with Professor Joaquin Ortega teaching at USC that summer, this was not an opportunity to be missed. After an overnight bus trip to L.A., he found himself a room in a flea bag hotel and phoned Professor Ortega, who invited him to a luncheon for faculty and students from USC and UCLA. There he found himself seated next to Louise Schrynemakers, an attractive young woman originally from Belgium, who had gotten her B.A. from USC in 1928 and was doing graduate work, majoring in French and minoring in Spanish. She had tickets reserved in the name of her employer, Mrs. MacNeil, to a performance at the Hollywood Bowl and Dwight was invited to join them. Another professor he knew at the luncheon was Dr. Osma from KU at Lawrence, who was teaching during the summer at USC, and by coincidence was renting a house next to that of Louise’s parents.

After returning to Madison, Dwight wanted to court Louise and thought the best way to do it would be by mail. He didn’t have the correct spelling of her name, thinking it was Schreim, and had to send his first letter to her probably care of the French Department at USC. Nevertheless, it reached her. This was late Fall of 1933 or early Winter. Louise’s interest in Spanish helped to cement their acquaintance.

They corresponded five or six months. Louise later would say that she had to have a dictionary next to her to be able to understand all the words in Dwight’s letters.

Finally, in late April or early May 1934, he proposed. Louse’s reply was “maybe” but “with a somewhat roseate tinge,” as he would describe it later. His proposal having been tentatively accepted, he set off for L.A. in his Model A Ford. The car probably looked much like this, but not as nice.

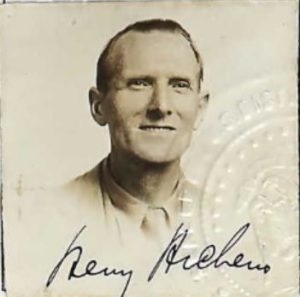

Louise’s two older sister had already been married some years, Mimi to Henry Hichens, a Cornishman who ran a bakery in East L.A., and Malvina to Marcel Cristin, a Frenchman who had lived many years in Belgium. Louise’s parents, Theodore and Ida, were by then retired and living in an apartment built for them by Henry on the top of his garage.

Police Suspect Dwight is Gangster “Pretty Boy” Floyd

Plans called for Dwight to meet Louise at her parents’ apartment in L.A. where she would introduce him to them, and presumably get their approval for the wedding. But a mistaken identity by police almost ruined everything. Dwight was walking down the street when two policemen in a passing patrol car spotted him. His youthful appearance reminded them of the notorious gangster, “Pretty Boy” Floyd, who would be named Public Enemy No. 1 by the FBI a month later and be shot down by police three months after that. The brazen robbery of a restaurant in the City of Pasadena earlier that day made the police think that “Pretty Boy” Floyd might have committed it and that this young man might be Floyd, notwithstanding his identification as Dwight Bolinger. They put him in the patrol car and off they went to Pasadena. Fortunately, the waitress who had been faced with the robber, said, “No, this is not the man!” Dwight’s remark to the police, “Sorry I couldn’t have been of help,” was not appreciated by the cops. But now Dwight had to call Louise and explain why he was late. This probably confirmed Ida’s suspicions about Dwight. Nevertheless, he and Louise were married July 1, 1934.

Some two weeks later Dwight and Louise are at Cañon, AZ visiting his aunt Grace and uncle John and their sons:

Louise’s Family History

Louise’s family was a mixture of Dutch, Belgian, and German ancestry. Her mother, Ida Moeren, was an ethnic German whose parents had moved from Xanten, Germany to the Belgian city of Liege in the 1850s where she was born and grew up. Louise’s father, Theodore Schrynemakers, was born in the Dutch city of Maastricht.

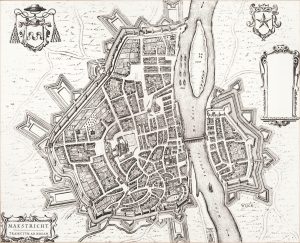

Maastricht is known for, among other things, the remnants of medieval walls, several towers dating from the 13th and 14th centuries, and the oldest gate in The Netherlands, built in 1230. It was the first Dutch city to be liberated by Allied forces in WWII (Sep. 13-14, 1944).

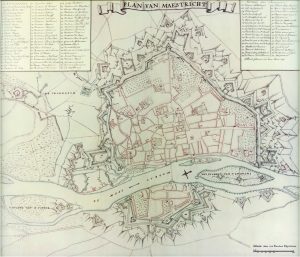

The following color map entitled Plan van Maestricht was originally done in 1753 by D.W.C. (David) and A. (Anthony) Hattinga.

Note how the Maas River (Meuse River in Belgium) flows through the city but with most of the city on the west side.

(Louise’s father’s youngest brother, Arthur (father of Arthur Britton), directed that when he died his ashes were to be scattered in Maastricht. Even though he had lived most of his life in Belgium and England, Maastricht meant that much to him.)

Louise’s grandfather, Reinhardt Charles Schrynemakers, was a shoemaker until, in the 1890s, the family moved to Liege where they managed the Hotel Allemand for several years. It was in Liege where Louise’s father, Theodore, and mother, Ida, met. He was helping in the hotel and she was working as a cashier in a shop, a job which required knowing the price of everything and making the sales calculations in her head. The minute Theodore saw Ida he knew that she was the woman he would marry.

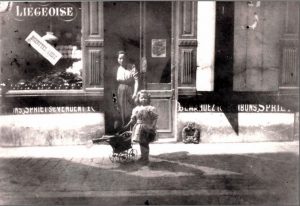

Theodore and Ida were married over her father’s opposition by posting the bans on a church in Bressoux outside of Liege where her father would not see them. Following their marriage they moved to Brussels where they ran a series of pastry shops. All three daughters, Mimi, Malvina, and Louise were born in Brussels. Below is their shop at one point, the Patisserie Liegeoise in Brussels, with Ida standing in the doorway and Louise’s oldest sister, Mimi, in front with her doll carriage.

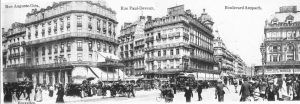

At one time their shop was diagonally across the square from the Bourse, the Brussels Stock Exchange.

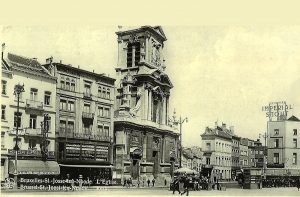

Another shop was a block or two from Saint Catherine’s Church next to what was then the fish market. Church records show the baptism of Louise’s sister, Mimi, at that church (see below).

Louise was baptized at the St. Josse Church in Saint-Josse-ten-Noode, one of the municipalities of Brussels where they were living at the time. See photo of the church below.

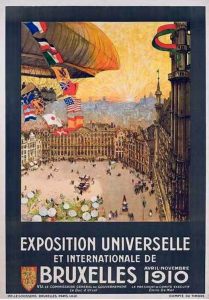

In 1910, Belgium held the Exposition Universelle et Internationale, or world’s fair, in the southern suburb of Solbosch. Twenty-six countries participated and there were 13 million visitors. A poster for the fair appears below.

Theodore thought that this would be an opportunity to earn some money by making cookies for the fair goers and sell them from a traditional dog-drawn cart. According to Wikipedia, carts pulled “by two or more dogs were historically used in Belgium and The Netherlands for delivering milk, bread and other trades.” “Carts drawn by a single dog were sometimes used by peddlers.”

According to his son-in-law, Marcel Cristin, Theodore rented a spot in a prominent location from which he could sell his cookies but then the entrance to the exposition was changed and he lost 50% of his investment.

By 1914, the family was living in Anderlecht, one of the municipalities of Brussels located in the southwestern part of the city. There they had a pastry shop with a corner location. They probably lived above the shop. Across the street was a Catholic school which Malvina attended and a short walk from the shop was a streetcar stop for trams to the center of Brussels.

With the beginning of World War I in August 1914, the family, because of its German family connections on Ida’s side, were in a precarious position. Not only did they have German relations, they had been hosting three German children who were cousins. When the US Embassy arranged for a train to take German women and children to the Netherlands, which was neutral, to be reunited with their families, Theodore was on the train with the children and reunited them with their parents.

In a letter to Dwight in 1934, Louise offered this tongue-in-cheek anecdote from when she was eight years old in 1914:

“The most touching recollections I have of my earliest childhood is the day I was sitting on my dear cousin’s back hitting him on the head with something suitably solid. While thus delightfully occupied, my sister came in and said there was a war on and that my cousin should immediately have his things packed and be sent back to Germany. This just goes to show you how a small, insignificant incident can sometimes cut short the most exhilarating moment of one’s life.”

Germany invaded Belgium on August 4, 1914, with the city of Liege falling to the German forces on August 7. Louise’s father, Theodore, who had been working outside of Brussels and concerned about the welfare of their relatives in Liege, went to check on them. He saw the destruction caused by the fighting. (For a thorough account of WWI and its impact on Belgium, see the documentary based on Barbara Tuchman’s book, The Guns of August.) His younger brother, Arthur, who was living in England, urged Theodore to bring his family to England. Reports of rapes of Belgian women by German soldiers added to their concerns, their oldest daughter, Mimi, being a very attractive young woman. Making matters worse, having lived with the German relatives for a few years before the war began, Mimi was very pro-German, even going to a German military camp outside Brussels to tend to the wounds of the German soldiers. If she was viewed as a collaborator, she and her family were in great danger.

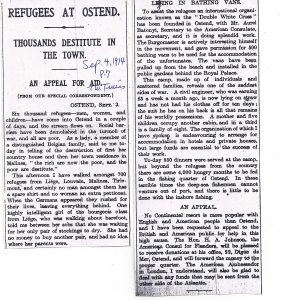

The Schrynemakers fled in September for England, abandoning their pastry shop and everything they could not carry inconspicuously, pretending to be going on a picnic. They took a street car as far as they could toward the North Sea port of Ostend, then rented an oxcart, which they shared with three other people, to travel the rest of the way. The following report in the Times of London dated September 4, gives some idea of the conditions in Ostend, the Belgian port from which they hoped to embark for England.

Their first destination was the English port of Folkestone. Thousands of Belgian refugees poured into Folkestone, some transported courtesy of the British Royal Navy, which brought them from Ostend. A report in The Times of London September 7, 1914 said

“The number of French and Belgian refugees has grown into a very serious problem. All sorts and conditions of men, women, and children are there. Hotels and boardinghouses are full, and the people are asking themselves, ‘What shall we do with the hundreds to come?’ Six steamers have arrived at Folkstone to-day from the Continental ports. Between them they have brought nearly 3,000 refugees, chiefly from Belgium. The representatives of the Home Office and the Folkestone Relief Committee are there almost every hour of the day; so too are the Consuls, and between them these authorities house hundreds of homeless families and dispatch hundreds of others to London.”

Folkestone later served as the primary embarkation point for British troops leaving for the front during WWI. The Scrhrynemakers family arrived at Folkestone on September 20, 1914.

In his history, Folkestone During the War, J.C. Carlile, describes the conditions of the refugees. “There were the mothers who had been hounded from home and country before they could gather the little ones to their arms. Their agony was intensified by the uncertainty of the fate of their children, and all means of communication was cut off…. And there on the quay was the most pathetic sight of all–little children clinging to big sisters for protection, or holding mother’s dress with trembling fingers. They drew back in fear at the sound of a stranger’s voice, as dogs shrink from those they distrust.” Carlile goes on to describe the response of the residents of Folkestone to the Belgians: “Fishermen’s homes were opened to people whose language they could not understand. Poor families shared with their strange guests, and some gave up their beds, counting it an honour to sleep on the floor that the exiles might spend the night in the comfort of home.”

After reaching London, Ida had difficulty persuading the authorities she was not a German and subject to internment as an enemy alien, but rather Belgian because of her birth in Liege or Dutch through her marriage to Theodore. Her photo from the ID papers issued her by the British show the strain she was under. The family story is that she camped out on the steps of an embassy, probably that of Belgium, until they ruled in her favor.

After arriving at the English port of Folkestone, the family first went through processing for refugees at Alexandria Palace in London.

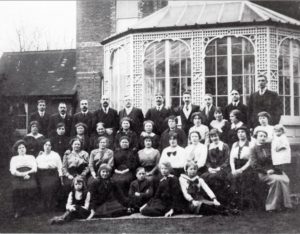

They were then dispatched to the town of Sutton in Surrey County where there was a stately home, Manor Park House, that had been set aside to house Belgian refugees. Toward the end of the time they were there in 1915, this photo was taken of them.

As Christmas 1914 approached, 8-year old Louise marveled at the magnificent Christmas tree at Manor Park House. But her parents told her that there would be no Christmas presents for her that year; they had lost everything and could not afford any presents. A woman supporter of Manor Park House, however, heard of the little girl who was not going to get any Christmas presents and resolved to do something about it. On Christmas Day little Louise went to the Christmas tree, even though she knew there would be nothing for her. To her utter amazement, she found a big doll under the tree with her name on it. For the rest of her life, whenever she would tell this story, she would weep with emotion. Eighty years later her son wrote a letter to the editor of the Sutton newspaper thanking the people of the town for the help they gave to his family so many years before. The letter, rather than being tucked away in a letters to the editor column, was made a front page feature story and launched an effort to identify the lady, but without success.

Minutes of the Sutton Belgian Refugees Committee, Oct. 1914- Oct. 1916 have one reference to the Schrynemakers, that of June 28, 1915, in which it is said that arrangements had been made for the schooling of the Schrynemakers children. Louise’s next oldest sister, Malvina, learned her English at Sutton School, according to Malvina’s husband, Marcel Cristin. Louise mentioned playing in the carriage house while the family lived at Manor Park House.

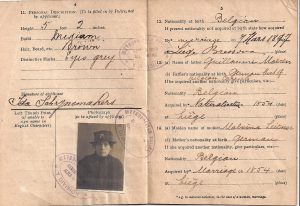

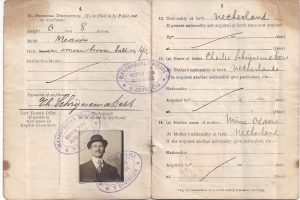

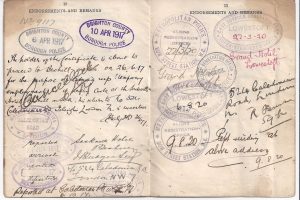

Theodore’s experience as a pastry cook probably was a big help as he sought employment. His identification booklet, stamped by the Metropolitan Police, Brighton County Borough Police, and the East Suffolk Constabulary, appears below.

The booklet shows Theodore working as a pastry cook at the Sackville Hotel in Bexhill-on-Sea in 1917 and the Grand Hotel in Lowestoft in 1920. Because of the distance from London, 52 miles for Bexhill and 104 miles for Lowestoft, Theodore obviously had to pay for his room and board in those towns while trying to save for the family back in London. The booklet shows a permanent address for him of 524 Caledonian Road, London.

For a time Ida and the three sisters lived with Theodore’s younger brother, Arthur, and his family. Unfortunately, Ida and Arthur’s wife, who was French, did not get along. Arthur’s wife did not like Germans and regarded Ida as German even though she was born in Belgium. A disagreement between two of the daughters of the women about a coat escalated into a row between the women and Ida took her family off to new quarters, probably the Caledonian Road address. Barry Hichens, son of Mimi, the oldest of the three sisters, recalled that Arthur had a chain of nickelodeons, the type of early movie house that charged an admission price of five cents, and that Mimi worked in the box office of one of them.

They lived in London from 1915 to 1920-21. During WWI, when the air raid sirens would go off warning of bombings by German planes or Zeppelins, they would hurry to the Underground for shelter. Two stories involve Louise’s next oldest sister, Malvina, who was 12 when the war broke out. One is that on one occasion the family was in such a rush to get to the underground shelter that Malvina was inadvertently left behind and they had to go back and get her. The other was that she got so fed up with the conditions in the Underground one night that she simply went home and slept the rest of the night there in her own bed in spite of the danger from the bombings. According to Malvina’s husband, Marcel, it was during the air raids that she developed her tachycardia, or palpitations of the heart.

The weather was cold and damp and there wasn’t enough food during the years in London. One of Louise’s memories of the time at the Caledonian address was being left alone sitting on the front steps eating liverwurst and margarine sandwiches, which left her with a loathing for margarine for the rest of her life. She also remembered being taunted by working class girls on the way to school where she had won a scholarship when she was still eight years old. For a class assignment she did a painting depicting a sad, lonely refugee child running which was based on her own experiences. Her teacher said it was remarkable and kept it. In her 1934 letter to Dwight, Louise recalled that period:

“As a good start to one’s education, England gave me a well-rounded inferiority complex and an acute case of shyness. Forgotten umbrellas, execution blocks for favorite historical characters and lifelike wax reproductions of the world’s greatest criminal are among my most vivid recollections of dear old England.”

Louise’s two older sisters, Mimi and Malvina, would go to different church services each Sunday, not because of any religious interest but rather because food was served after services. Their favorite was the Rosicrucians who had the best food!

During this period Louise attended school, learning English in addition to her other subjects. Malvina, who turned 17 shortly after the end of WWI, learned the millinery trade while in London, which she put to good use later when they were in Los Angeles. Perhaps here is a good place to insert Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec’s 1900 portrait, The Milliner.

By the end of WWI, Mimi had turned 20. Her son, Barry, recalled the following: While living in London, she had two successive jobs. The first was working for a French or Belgian family in a patisserie. She sold coffee and pastries, waited on tables, and worked behind the counter. It was hard work, 12 hours a day with only a half-day off a week, and most of the time she was on her feet all the time. The shop had an upscale clientele. One attractive feature of the job was that many Belgians patronized it. It was there that she came to dislike the British because of their attitude toward anyone who spoke a foreign language. It was also there that she came to like the Americans.

According to Barry, Mimi left the job at the patisserie and went to work as a clerk-typist “spy” for an import-export business that dealt with the Belgian Congo. She was hired because she spoke French and German and the fact that she did not know anything about typewriters was not an obstacle. Barry thought that there probably was a lot of commerce between warring factions.

During the time she worked at the patisserie, she became friendly with an American customer whose son was in Los Angeles. A picture postcard from the son, which the customer showed Mimi, depicted the sunny orange groves. It might have looked like this one:

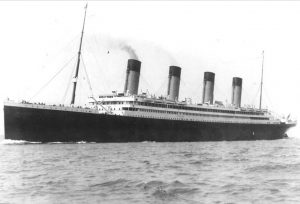

Mimi resolved that the family would move to L.A. They originally planned to leave together but had difficulty getting passage. Finally, when they found two cancellations, Mimi and Malvina left on September 29, 1920. According to Greg Hichens, they sailed on the RMS Olympic.

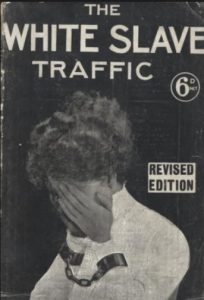

After arriving in the U.S., they traveled by train across the country with a change of trains in Chicago. Mimi’s son Barry recalled her mentioning several times that she and Malvina were picked up, probably at the train station, by a policewoman who said, “I will stay with you until you get back on the train.” Mimi would have been about 22 at the time. Barry speculated that the policewoman’s action may have been prompted by the risk of young women being grabbed by white slavery rings. The news story below shows that two unsophisticated young immigrant women could have been at risk.

After arriving in California, Mimi and Malvina first worked in a hotel in Pasadena as chambermaids. The owner, who also owned a hotel at Lake Tahoe, offered them a chance to work there, probably during the summer of 1921. The two attractive young women with their foreign background, were popular with the cowboys at the hotel, who took them on a ten-mile horseback ride, the “ride from hell” as they remembered it, because they had no experience riding and were not in condition. Part of their earnings probably went back to the rest of the family in London. Theodore followed in 1921 on the R.M.S. Saxonia, arriving January 21, according to his declaration of intention to become a U.S. citizen.

Ida and Louise followed in July on the RMS Berengaria. The family had arrived!

Theodore went to work for a Cornish bakery owned by Henry Hichens. It was through this connection that his and Ida’s oldest daughter, Mimi, met Henry. They married and had two sons, Ralph and Barry. Their descendants live in California and Seattle. Henry was from Newlyn, Cornwall. A modern day scene of Newlyn appears below:

Henry Hichens was born in the fishing village of Newlyn, Cornwall on October (or November) 19, 1886. According to Greg Hichens, Henry’s mother, Sarah Kitchen, was first married to a man whose last name was Sampson with whom she had two sons. Her second marriage was to Henry Hichens, a fisherman, and it resulted in two children, Sarah and Henry. According to Greg Hichens, Henry taught school for awhile and then traveled to South Africa with his close friend Thomas Treleven who was also his brother-in-law. (Tom was married to Henry’s sister, Sarah.) While in South Africa, Henry lived with a half-brother of his, who may have owned a bakery. Greg Hichens remembers a folder that Barry Hichens had containing a photo taken of Henry and Tom in South Africa along with a South African government travel pass. Following a return to Cornwall, Henry emigrated to the U.S. along with Thomas Treleven on the SS Philadelphia. The ship’s manifest shows them as arriving in New York City on July 5, 1913 on the SS Philadelphia. Henry would have been 26.

At some point Henry gave up the bakery business and appears to have focused, instead, on decorating cakes, including wedding cakes. In his 1939 declaration of intention he listed himself as “cake decorator.” His WWII draft registration card lists his occupation as “self cake decorations”. His nephew, Bruce, visited Henry and Mimi at their home in Fullerton in the early 1950s and remembers watching Henry decorating a cake and marveling at Henry’s artistry. According to family stories, Henry was very popular among Hollywood stars, among them Shirley Temple, who would order their cakes from him. Bruce also remembers an early morning walk with Henry on the hills around his property. The mist was just beginning to clear and Henry described the different types of animals that lived there. It was a “magical moment” according to Bruce.

Henry’s grandson, Greg Hichens, remembers that when Henry and Mimi lived at their Fullerton house Henry would tend the many fruit trees on their property. Mimi would squeeze fresh orange juice for breakfast. For lunch he remembers having avocado sandwiches and sitting on the back porch with Mimi while she shelled peas from the pod.

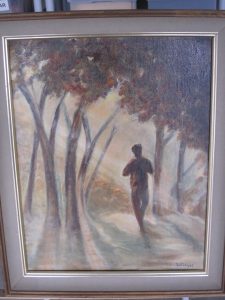

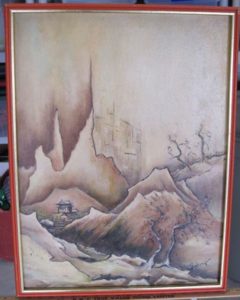

In addition to expressing his art in decorating cakes, Henry painted outdoor scenes. The following are paintings by Henry in the possession of his grandson, Greg Hichens.

Marcel Cristin, a Frenchman, who had been living in Brussels, faced with being drafted into the Belgian Army in the 1920s, decided to emigrate to America instead. Marcel mentioned his plans to his shoemaker, Jean Schrynemakers, an older brother of Theodore, who told him of the Schrynemakers relatives in Los Angeles, a family with three daughters, two of them of marriageable age. Following his arrival in L.A. , Marcel made arrangements to meet the family. Apparently the idea was to marry him off to Mimi but it was Malvina who, as fate would have it, answered the door. They subsequently married and had a son, Raoul, and a daughter, Yvonne, who are both living and have family in California.

Malvina loved to act and had hoped to become an actress. Her daughter Yvonne recalls how one time she was to be the narrator introducing a school play and it was Malvina who instructed her in the gestures and choice of wording to use.

Returning to our story of Louise, in her letter to Dwight from 1934, she described what happened next:

“At fifteen I set forth to conquer the world. I had the temerity to lie about my age; became a nurse in a private hospital, and with the best of intentions nearly killed all the patients. After which noble exploit my parents prevailed upon me to return to school.”

Louise completed high school in Los Angeles, then enrolled to work toward a B.A. at the University of Southern California. She describes that experience thusly:

“At college I followed a thorough course in the intricacies of apple polishing with fairly successful results. And …. here I come to the most shameful part of a very shameful confession: I fell deeply and desperately in love with every single one of my professors, not one escaped. The older and homelier they were, the more infatuated I was. I still have somewhere the drawing I made of my Psych. prof. It is the picture of a trained seal dressed up like the prof. Unfortunately other students saw it and several suffered from choking fits shortly after. Having so advantageously spent my time at college, I emerged completely cured and said, ‘Never again!”

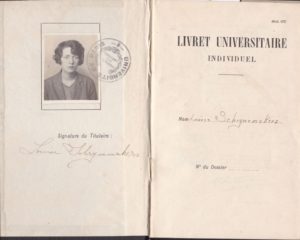

Louise graduated from U.S.C. in June 1928. On October 24, 1928 she enrolled at the University of Paris, also known as the Sorbonne, where she took the following classes:

- History of Literature of the French Renaissance

- French poetry, Moliere’s play, ‘L’Ecole des Femmes“

- Literature: Montesquieu, his life and works

- French Literature: “Le Parnasse” (an anthology of poems)

- 17th Century: the novel

- Spanish literature

- Rousseau’s “Dreams of a Solitary Wanderer”

The photo page of her university booklet appears below.

At that time she was living at 5 Impasse Royer Collard, Paris (5e). The address still exists and thanks to Google, we can see the type of neighborhood, with its multi-story apartment buildings.

Her time at the Sorbonne was abruptly brought to a close when she received a telegram from Ida urging her to come home because Theodore was ill. As it turned out, Ida was simply lonely and there was nothing wrong with Theodore. Louise never returned to the Sorbonne but did continue with her studies at U.S.C., which is how she met Dwight.

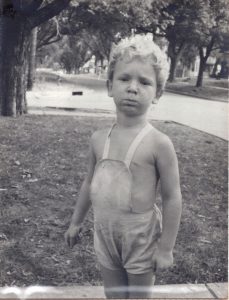

After their marriage in L.A., they settled in Madison, Wisconsin where Dwight was finishing his doctorate and teaching. Their first child, a boy, named Hugh Clyde (later renamed Bruce Clyde), was born in 1936. To send a telegram in those days was too expensive for their budget. Since their son’s middle name was the same as a seaport, Dwight took advantage of a Western Union bon voyage message rate and wrote “A safe arrival to Clyde and a nine-pounder salute from us. D.B. Motherwell.”

At times, he looked like a child any mother could love.

Or not.

Much later:

For information on Bruce’s career, click here.

The second child of Dwight and Louise was Ann Celeste, born near the end of 1948 in Los Angeles when Dwight was teaching at USC.

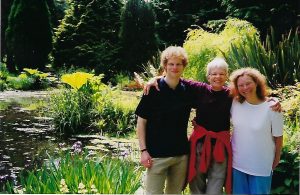

The three sisters:

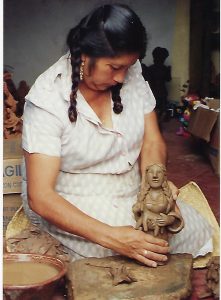

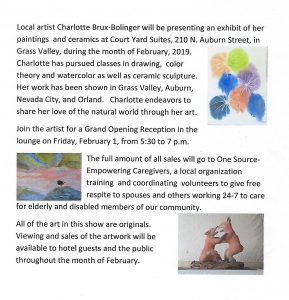

One of the ways in which Louise expressed her love of art was through painting and sculpture. It began at least as early as the family’s days in L.A. when Dwight was teaching at USC and Louise took an art class, certainly by 1959 when Louise’s daughter, Ann, was 11. It continued in Boulder, Colorado, where she had a good instructor. Louise really got carried away with painting in Colorado because she could go outdoors. Once she took her easel and brushes up into the nearby foothills of the Rockies to capture some of the scenery. Having set up her equipment, she was deep in concentration when she heard a noise behind her. Turning around she found herself facing a bear. Her easel, paints, and brushes were left behind in her mad dash to put some distance between her and her unwanted fan. In Belmont, Massachusetts, Louise used the basement as a place to work on her sculpture. And in Palo Alto, it was through an art class that Louise met Shirley Ortiz who would become her closest friend.

Here are some samples of her work.

Ann’s Artwork

Probably inspired by Louise’s love of art, her daughter Ann McClure is a member of an art class that meets weekly in Stonehaven, Scotland. A painting Ann did in 2019, a copy of a work by Edward Seago, appears below:

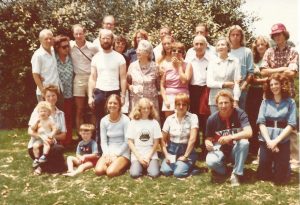

Schrynemakers 1976 Family Reunion

Schrynemakers 2006 Family Reunion

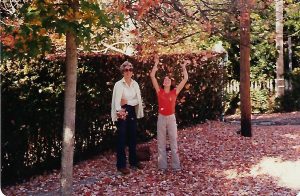

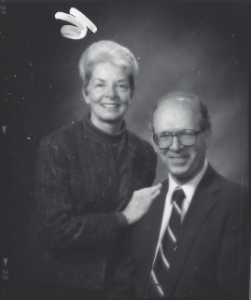

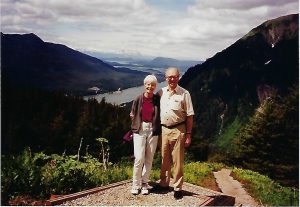

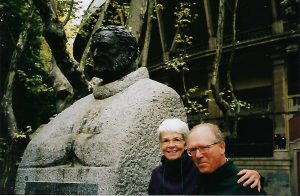

Bruce and Charlotte

Bruce and Charlotte met at a holiday party in December 1979. They were married August 24, 1980.

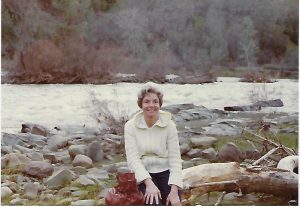

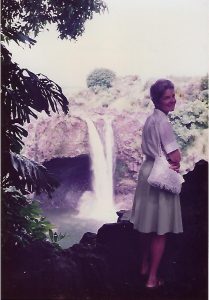

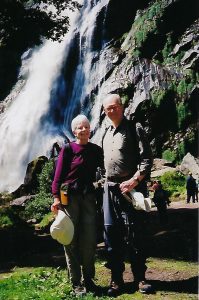

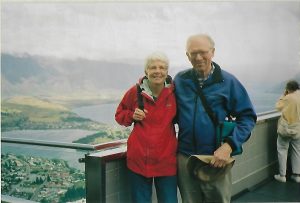

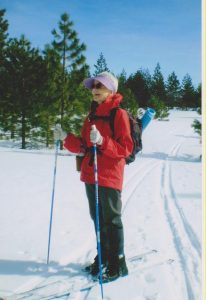

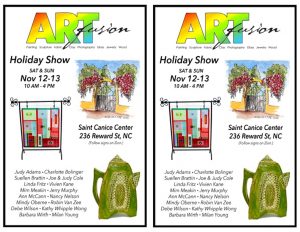

The following are photos of Charlotte and their life together.

Charlotte in the cramped five-wheeler in which we lived during the 2000 house remodeling of our house on Banner Mountain. Note our cat George on her back.

This page remains under construction.