During the years Dwight spent at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles he advanced quickly through the ranks: Assistant Professor (1944-1946), Associate Professor (1947-1948), and Professor (1949-1960). Within two years of arriving, Dwight was appointed Chairman of the Department of Spanish, Italian, and Portuguese.

A news story in the Los Angeles Times, Dec. 8, 1952, shows how the USC faculty interacted with the larger community. The headline read, “SC to Hold Festival of Spanish Music.” It went on to say, “A Festival of Spanish Music, Dance and Costume will be held Thursday at 8 p.m. at the University of Southern California. The festive program is sponsored by the university’s Spanish department and the Spanish consulate of Los Angeles. Principal speakers will be Dr. Dwight L. Bolinger, head of the SC Spanish Department; Jose Perez del Arco, Consul of Spain in Los Angeles; and Dr. Laudelino Moreno, a professor in the Spanish department at SC. Exhibitions of Andalusian and Basque dances are scheduled, along with songs and music of Spain. The public is invited to attend the program without charge.”

Sometimes conferences required cross-country travel. During a visit to Topeka in 1951 after Dwight, Louise, and their daughter Ann had been to a language convention in Indiana, W.G. Clugston remarked on what he thought their “bizarre form of transportation.” “The family traveled all the way from California to Indiana and back in a little Crosley car, with bedding equipment, cooking utensils and a well-stocked larder stowed away inside and on top. Yes, they averaged better than 35 miles to the gallon–and saw valley beauties and mountain splendors from a angles that fast-moving tourists in big cars can never enjoy.” (Topeka State Journal, May 19, 1951, pg. 12.)

Pronunciation of “Los Angeles”

After years of debate as to how to pronounce “Los Angeles”, in 1952 Mayor Fletcher Bowron established a committee made up of some 20 community leaders, radio announcers, newspapermen, historians, pioneer Los Angeles families, etc., to determine the correct pronunciation. “Many versions were considered, but the issue settled down between the hard ‘g’ and the soft’g’ in juh.” (Los Angeles Herald-Express, Sept. 13, 1952). Dwight was instrumental in the choice of “Loss AN-ju-less.” According to a report in The Times (Sept. 13, 1952), “The phonetic symbols were decided by Dwight Bolinger, University of Southern California Spanish professor, who said that from a Spanish language standpoint, the pronunciation is not as much at variance with the true Spanish as that employing the hard ‘g.’ ”

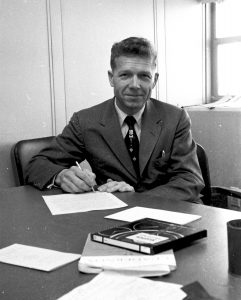

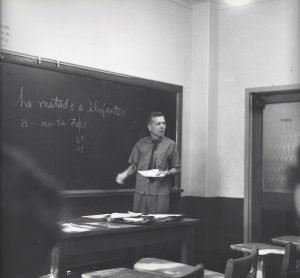

Occasionally, the universities where Dwight taught found it useful to take formal photographs of him. Here is one taken by USC dating from December 1954.

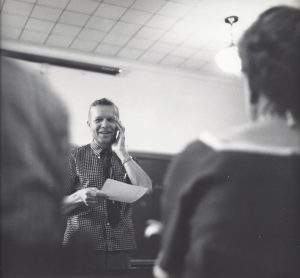

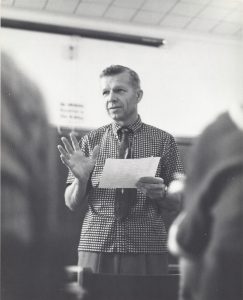

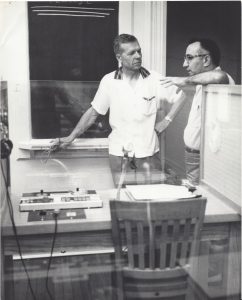

And this next one, taken in November 1957, shows Dwight when he took on the federal government to save the five Spanish sailors (for more on that subject, see below).

National Defense Education Act Visiting Linguist

During Dwight’s affiliation with USC, he was away for two periods. From 1956-1957 he was a Research Fellow at the Haskins Laboratories in New York. Click here to view the portion of this website about that. The second period when Dwight was away from USC was in 1959 when he was a Visiting Linguist at the 1st NDEA Institute, University of Colorado, Boulder. This was also an opportunity for the university to look him over and probably led to his being offered a professorship in 1960.

The Case of the Five Spanish Sailors

“Dear Fellow Hispanists: In June and July of this year occurred a series of small events with a large human import and a larger significance for us as mediators between Americans and the peoples who speak Spanish.” Thus began a letter written by Dwight in October 1957 on behalf of five Spanish sailors who had deserted from their training ship after it docked in San Diego, and who had crossed the border into Mexico. No doubt a factor in their selection of Mexico rather than some other Latin American country was that it had supported the Spanish Republican government during the civil war and still did not have relations with Spain, then still under the Franco dictatorship. They probably hoped that they would be given political asylum and allowed to remain there rather than be returned to Spain. But they had no contacts in Mexico, were picked up by the Tijuana police, and moved back across the border into the US. The letter, signed by Dwight and 25 other teachers of Spanish and Portuguese, was probably mailed to the entire membership of the American Association of Teachers of Spanish and Portuguese (AATSP), in which Dwight was active. Click on the following to view the letter: Dwight’s fund-raising letter on behalf of the 5 Spanish sailors.

The letter spells out many of the details of the case but not all. It was Dwight who, after reading a tiny news item in the Los Angeles Times about the Spanish sailors being in U.S. custody, contacted A.L. Wirin, the noted civil liberties attorney of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) of Southern California. Wirin took immediate legal action to obtain a last minute restraining order blocking return of the sailors to their ship. The sailors were on the dock about to be returned to their ship when the restraining order reached the Navy, stopping any further action. What happened next was that Dwight, Wirin, Professor Laudelino Moreno of the USC Spanish Department, and Dwight’s son, Bruce, took the train from L.A. to Santa Ana where they met with a retired Marine Corps officer who gave them advice on how to obtain permission from the Navy, the custodian of the sailors, to meet with the Spaniards. Until the little delegation could meet with the sailors and persuade them to authorize the ACLU to represent them, there was nothing legally that could be done to help them. Professor Moreno, a native Spaniard and former diplomat of the Spanish Republic, was of particular help because he could put the sailors at their ease. The sailors were happy to have the help and signed up. There followed months of legal proceedings and a campaign to make the public aware of the facts of the case. Among the people recruited by Dwight to support their cause was Rufus B. Von KleinSmid, Chancellor of USC, and Frank Baxter, noted TV personality and Professor of English at USC. Even the political columnist Drew Pearson picked up the story. As part of the campaign, Americans were urged to write letters to John Foster Dulles, Secretary of State, and William P. Rogers, the United States Attorney General.

One of the legal issues in the case was the applicability of a 1913 treaty between the United States and Spain, then still a monarchy. One of its provisions called for reciprocal return of deserters. But the crew of the Spanish ship had been given leave to visit San Diego. Consequently, while the sailors were in the San Diego area, whatever their intentions, they had not deserted. But when they stepped into Mexico, they had. But Mexico not only had no such treaty, it did not recognize the Franco regime. A.L. Wirin argued, among other things, that the treaty did not apply to the Spanish sailors because they deserted in Mexico, not the United States. And the circumstances of their return to the U.S. were most peculiar (see Dwight’s letter).

During the legal proceedings in the U.S. District Court in Los Angeles, a representative of the Mexican government dramatically announced that the government of Mexico would welcome the five Spaniards. Even the prelate of the Roman Catholic Church in Baja California gave his support to the sailors. Ultimately, the five Spanish sailors won their freedom to enter Mexico. The last article to appear about them in the ACLU newsletter showed them waving a happy goodbye as they crossed into Mexico.

A side note: actually there were six sailors who deserted, not five. But the sixth had a girl friend in San Diego and may be there even now!

MLA Modern Spanish Textbook

In his personal essay, “First Person, Not Singular,” p. 34, Dwight explains how Modern Spanish came about:

“…Sputnik hit the language-teaching profession like a misguided missile. The U.S. was losing its lead. The National Defense Education Act was set up to get things moving in science, mathematics, and foreign language. Bill Parker, Director of the Foreign Language Program at the Modern Language Association, asked me to head up a committee to write a textbook that would break away from some of the anti-linguistic traditions that kept repeating themselves in one book after another. The idea of the project was to put the pressure on publishers by producing a text that would be officially sponsored by the Association but let out for bids by commercial publishers–in hopes that competition would then force other publishers to follow. The scheme was fairly successful and the resulting text, Modern Spanish, was an important part of the audiolingual revolution—what was unjustifiably called by some people at the time the ‘linguistic method’.”

The following article appeared in the Daily Trojan, the USC campus newspaper, on Nov. 25, 1957:

By the spring of 1958 Dwight was in Austin, Texas, working on the project that eventually became Modern Spanish. Here is a rare photo of the working committee members conferring on it.

Two newspaper accounts of the work on the book appear below.

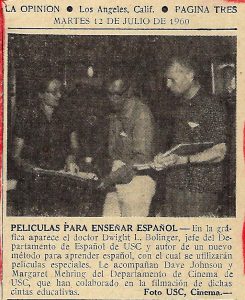

1. La Opinion, July 12, 1960, pg. 3, Los Angeles Spanish language newspaper, “Candilejas Ideas… y Television”, “Limelight ideas… and television”, by Othon Castillo

Photo caption: “Films to teach Spanish – In the image appears Dr. Dwight L. Bolinger, head of the Department of Spanish at USC and author of a new method to learn Spanish, with which special films will be used. He is accompanied by Dave Johnson and Margaret Mehring of the USC Cinema Department, who have collaborated in the filming of these educational films. Photo USC Cinema–”

“The learning of a foreign language brings with it a series of problems that often disorient the novice teacher. There are deep psychological and physiological factors that intervene in this learning. One of these, perhaps fundamental, is the way of using the tongue and lips in the formation of words. Since in each language these phonetic means are employed in completely different ways.

“Dr. Dwight L. Bolinger, head of the Spanish Department of the University of Southern California, who for two years has worked as the head of a group responsible for developing a new text for learning Spanish in educational establishments of the United States, based on the factors that we have previously raised, had the original idea of using cinematographic films, not just as a method in itself, but as a means to arouse interest in students from the outset, using them, in addition, like that step of the lesson that in didactic is called motivation. Through “Close-ups”, the students will be able to appreciate the way of pronouncing of the actors and the position of the parts of the mouth and tongue.

“The National Defense Education Act has sponsored this original project of Dr. Bolinger’s, for which he has been allocated the sum of … $ 63,000, the films must be completed by next September. The first film will be used to do test research this summer, in 10 or 12 schools in different parts of the United States.

“Paramount Pictures has collaborated in the filming of these movies, providing the necessary props; as well as Dave Johnson and Margaret Mehring of the USC Department of Cinema serving as advisors to Dr. Charles N. Butt of Los Angeles State College, Othón Castillo of La Opinión, Jose L. Gimeo and several language teachers. For these films, more than 30 Hispanic-American actors from different places have been used, in order to give the student the opportunity to listen to the different accents of the Spanish language.”

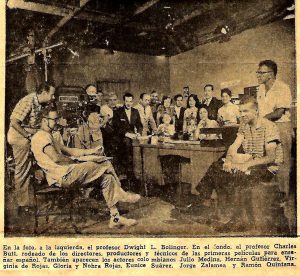

2. “El Espectador” (Colombian newspaper – Bogota?), July 17, 1960, “Enseñando Español por Medio del Cine,” Teaching Spanish through Cinema” by Ines de Montaña, Correspondent for The Spectator in Los Angeles

“In photo, at left [lower right corner], professor Dwight L. Bolinger. Background, Professor Charles Butt, surrounded by directors, producers and technicians of the first films for teaching Spanish. Colombian actors Julio Medina, Hernan Gutierrez, Virginia de Rojas, Gloria and Nohra Rojas, Eunice Suarez, Jorge Zalamea and Ramon Quintana also present.” “Colombian Actors Participate in the Sensational Experiment to Streamline Language Learning in the United States. What are the foundations of the New System?”

“Next fall, when school work begins, an important test will be carried out at several universities in the United States. The aim is to add to the teaching of Spanish the projection of a series of short films and to see if, by this means, better results are obtained in the learning of foreign languages. The matter is of great importance. Ever since humanity has suffered the consequences of the “Tower of Babel” the difficulties encountered in spoken communication are immeasurable. In times past – when distances existed – it was not as imperative as today, to learn other languages. But in the era of the Jet – and in the next era – the need to learn a language other than the native one has emerged. You all well know this, and nowadays the subject is a constant topic of discussion. Your correspondent [Inés de Montaña] is taking this on because movies can be a great advancement in language learning. It has fallen to the language of Castile to be chosen for the project and because, among the small group of actors who work on the films, there is a great majority of Colombians.

“One fine day at the University of Southern California, we learned that the film clips would be shot in Spanish, along with the names and nationalities of the stars. Soon afterwards we obtained more reports, along with an invitation to see work being done on one of them. So it was that one morning we visited the campus of one of the oldest and most prestigious higher education institutions in the American West. Meadows – very green this time of year – and trees surround the buildings of USC. Some are imposing, others less so. But in all you breathe the same atmosphere, and from there you can see young boys and girls of different nationalities and races with books in their hands.

“At the corner of one of the running tracks on the University of Southern California campus, we encountered a group of people. There were cameras, light reflectors, and, on the wall, notices in Spanish. It was supposed to be a street in Buenos Aires where a vendor, in front of a cart full of bananas, attended to the large group of American tourists. After making their purchases, they asked for information about how to get to the city center by bus.

“The episode is among the so-called “Problems of the Tourist”, because the travelers didn’t even know the Argentine currency and what buses are called in Buenos Aires. On this occasion, the most important speaker was Julio Medina, the young Colombian artist who years ago came to study drama, and who is already reaping the fruits of his efforts. Another scene took place in front of a newstand. Hernán Gutiérrez, a well-known broadcaster from Bogotá, has come to specialize in the art of filmmaking, recently achieving the status of a successful television producer. He is an actor too, and he’s carrying an edition of El Espectador, so the Spanish students of the United States would see the name of the Bogota newspaper in the movies. Along with each of them, the compatriots Oscar Alvarez, Virginia de Rojas and their daughters Gloria and Nora, Eunice Suárez and Jorge Zalamea have collaborated on this important educational activity. There’s also Ramón Quintana, of Mexican nationality, but who was born in Bogotá. All have produced excellent results, according to the directors.

“On the morning we were at the University of Southern California, we were able to speak with and watch working professors Dwight Bolinger and Charles Butt. Once again we admire the down to earth American professors. These two, in sport shirts, under a full sun, worked hard alongside the filming technicians. The scenes have to be repeated not once, but ten times. Then it’s necessary to listen to the recording, and then do it again if it has the slightest defect. In this case, the text must be absolutely identical to that of the book, on which this new method of teaching Spanish in the United States is based.

“Professor Bolinger, who speaks a perfect Castilian, with the accent of our mother country, told us of the vast projections of what we were watching. “It is a fact that there is a serious problem with the delay of the application of linguistic science and pedagogical sciences in the teaching of languages. To address this issue, in 1956, a meeting of Spanish professors was held in order to see if it was possible to improve the texts. It is well known that publishing houses do not want or cannot get away from tradition, under pain of not selling their product.” We learned that the professors realized that this was the biggest obstacle that had to be overcome. The assembly ended by recommending to the Modern Language Association the undertaking of the task of writing a textbook with all the latest advances of the teaching system. Getting down to the task, a committee of 25 Hispanists and another of six writers was founded. Of the latter, one was named president: the kind professor who has shared all of this interesting information with us.

“The Rockefeller Foundation donated $237,000 to the Modern Language Association and, drawing from these funds, several meetings were held for consultation in 1956 and 1957. In 1958, invited by the University of Texas, “we settled in Austin and dedicated ourselves to composing the first version, with funds from the Rockefeller Foundation, for salaries and other expenses.” In June they will deliver the original to the MLA. The latter submitted it to several publishers to get the best offer. Harcourt Brace and Company emerged victorious in this small contest and the book that was published two months ago has already been adopted by some 40 universities. They informed us that they are already using the text in the current summer courses, but their biggest job will start in September. Along with the book there are discs and content tapes. Something exemplary worth mentioning is that the professors who worked so long with not very high salaries – and who have put into the effort the fruit of their studies of years – totally renounced the royalties of the work. All these pass to the MLA and will be used in the editions of similar texts that teach other languages. It is clear that if they did this work in the private sector, thousands of dollars would have made its way into their pockets. But for these scientists, money does not matter. For them, what matters is to fulfill the noble teaching mission that has been granted them. Here we can point out that what is attributed to the American people with respect to “money, money, money” is far from accurate in many sectors.

“In addition, Professor B tells us that the idea of filming was not part of the original plan. “Of course there has been this core idea for I don’t know how long, but there were no means for its realization.” Now, with the approval of the NDEA, there are now funds to improve instruction in terms of languages. The University of Southern California got the approval of a bill to make films related to the new text, and submit them to a series of tests to prove their usefulness.

“For the reason previously noted, they sought Spanish-speaking actors, and among them were chosen this group of our compatriots who work with keen interest and success, which we’re very pleased to share with you.

“They and their voices will serve in an investigation that can transform the teaching of languages through cinema and the first stars are, for the most part, Colombian.”

Robert Stockwell on the Modern Spanish project

Robert Stockwell, in his obituary of Dwight, p. 107, said “I am certain that all who worked on it would agree that the success of the cooperative enterprise was due overwhelmingly to Bolinger’s leadership.”

Presidency of American Association of Teachers of Spanish and Portuguese

Dwight was active in the AATSP early on. An article in the Albuquerque Tribune of Dec. 14, 1940, reported that he was one of three speakers at their annual meeting. Similarly, the New Orleans Item of Dec. 20, 1950, listed him as one of four speakers on the first day of that year’s convention. In 1960, Dwight was elected president of the AATSP. A report in the Daily Trojan (Jan. 5, 1960) reporting his election, noted also that he was “instrumental in the establishment of SC’s new language laboratory.” A news story about the conference said that Bolinger told the delegates “of their moral and intellectual responsibilities as teachers.” He said that “their role is twofold in that they not only must convey instruction in the learning of a second language here, but also must be aware of the scrutiny of Spanish-Americans living in this country.” By then 139 publications were to his credit, including some three dozen articles related specifically to Spanish plus four books, Intensive Spanish (1948), Spanish Review Grammar (1956), Interrogative Structures of American English (1957), and Modern Spanish (1960). The presidency of AATSP was probably a recognition of his prominence in the field.

Decision to Leave Los Angeles

In 1960, during a working session with some of his colleagues, Dwight suffered what appears to have been an ischemic stroke in which his left arm went numb and briefly he could not speak. However, he never lost consciousness. His colleagues rushed him to the nearest hospital, where he had a quick recovery. At that time he was filming the scenes used in the Modern Spanish textbook as well as teaching. Fed up with Los Angeles traffic and pollution and with his health in mind, he both drastically changed his diet and welcomed an invitation to teach at the University of Colorado at Boulder. It also would be an opportunity to work with the French phonetician Pierre Delattre, with whom he had collaborated at the Haskins Laboratories in 1956-57.