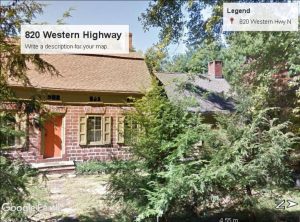

During Dwight’s affiliation with USC, he was away for two periods. From 1956-1957 he was a Research Fellow at the Haskins Laboratories in New York. During this period, Dwight, Louise, and their daughter, Ann (ages 7 to 8), lived in Blauvelt, New York, in a home that was said to have belonged to George Washington’s gunsmith. Research by Ann McClure found that Abraham M. Blauvelt repaired guns and watches in this house around Washington’s time, and rented boats on the Hackensack River in the rear (where she fell through the ice!). The Blauvelt family occupied the house for 135 years. She felt that his had to be the house where she and her parents lived because of (1) the gunsmith story, (2) the small unusual openings over the front windows, which she recognized, and (3) what looks like what might have been the barn to the right and behind the house — its correct position in her memory, and note the large chimney that could be for a barn.

Each workday morning, Louise would drive him to the train station from which he would travel to Nyack. Next came the ferry to New York City, probably Yonkers, and, finally, by subway, taxicab, bus, or on foot to the Haskins Laboratories. This period was an opportunity for Louise and Ann to explore the city. Ann remembers visits to the Museum of Modern Art and the Empire State Building. While on a trip to the former Ann lost her purse and while at the museum went from exhibit to exhibit with her mind on other things. She finally burst out with, “All this stuff and not one shrunken head!”

A fond memory of their home in Blauvelt was “Josephine”, the chicken who came with the house. “Josephine” liked company and would perch on their porch railing to be near them. Writing on Oct. 6, 1956, Dwight wrote to his father, AJ Bolinger, “Did I tell you that we have one hen, who is queen of the walk? A Buff Orpington, I think. She delivers one egg a day. Unhappily she has a taste for wild onions, and our eggs come pre-seasoned. The first good frost should take care of that.” Writing again on Nov. 16, 1956, he said, “Did I tell you that Josephine perches on the railing of our front stoop, where she can peer in the window and watch us at night? It also puts her at advantage in the morning to cluck for her breakfast.” Sadly, poor Josephine was killed by a snake after they moved back to Los Angeles.

In a letter Dwight wrote Sep. 22, 1956 to his father, he described his first impressions of the Haskins Laboratories:

“I went in to town for the first time Thursday. It is a tedious trip and I don’t have the hang of it yet. Most of my time has been spent watching one of the old-timers work at the machines, especially the pattern-playback, which sythesizes artificial speech. The men doing the speech work here have been mostly engaged in trying to find what are the signal-carrying parts of what we hear. A picture of live speech shows a lot more frequencies of sound than are needed to convey a message, and they have been slowly stripping it down to minimal essentials.

“Their work has commercial applications in telephonics in that it points the ways for narrowing the channels that have to be used in communication–this enables the telephone people to transmit more on their cables while charging you and me the same rate. Actually the Bell people have not used Haskins research to any extent yet, though there is some connexion–not a financial one, however.

“I feel an awful ignoramus. The people here are all technicians. My approach, event to intonation, which they are interested in and which is why they brought me here, has been grammatical rather than instrumental. I expect to learn a lot if I can keep afloat, but I don’t know how much if anything they are going to learn from me.”

In a letter to his father on Oct. 24, 1956, Dwight had this to say:

“At the lab I’ve been synthesizing intonations, on some words that Dr. Delattre had, in turn, synthesized for me. I trying to find out how much stress owes to pitch, and being able to control the pitch by watching a meter cuts out any funny business with cues that you don’t want creeping it. Delattre can make some mighty realistic speech with his painted diagrams.”

Writing on Jan . 19, 1957, also to his father, Dwight said:

“Monday I go to Yale for a talk at the Linguistics Club on the research I have been doing at Haskins. The lab people are really swell. I rehearsed the paper yesterday and the day before with them, and they are practically stopping operations Monday morning to get me the tapes and duplication that I’ll need. I’m going to try to launch a theory of pitch accent. Without champagne, the Yale people can scuttle anything.”

Dwight and Louise’s son Bruce remembers visiting Dwight at the Haskins Laboratories. The equipment Dwight was using reminded him of cartoons of that period of computers, with an imposing bank of switches, dials, speakers, and the like. Dwight was working with a clear plastic belt that passed over two spools and under an electric eye. The belt was subdivided into sections, the sections representing different sound frequencies. When Dwight first operated the machine for Bruce the speaker produced a robot-like voice with no intonation whatsoever. Then, after Dwight added a few brush strokes to the appropriate sections on the belt, the voice from the speaker began to sound like an ordinary human’s voice.

The following is an article that appeared in the Daily Trojan, on April 10, 1958, entitled, “Bolinger to Speak at Event”:

“Dr. Dwight L. Bolinger, head of the Spanish Department, will speak at the graduate school’s annual Research Lectures to be held April 18 and 6:30 p.m. in the Town and Gown foyer. Dr. Bolinger’s lecture is entitled “Machines That Talk.”

“The series of lectures was inaugurated in 1933 under the auspices of the Graduate School. The lecturer is chosen each year by a committee of the faculty of the Graduate School.

“Worked With Sound

“During 1956 and 1957, Dr. Bolinger was invited to engage in research activities at the Haskins Laboratory in New York City, a research center established to help the blind.

“Dr. Bolinger had done research on the nature of intonational patterns, pitch, inflections and their relationship to meaning in languages in general.

“His investigations led him to believe that there is a relationship between the basic elements of speech and the expression of common human emotions, regardless of differences in lexicon, semantics or structure.

“Theories Tested

“His articles to this effect prompted the Haskins Laboratories to invite him to use their facilities in order to test some of his theories regarding language, since the sightless must depend to a great extent on sound. Experiments on the sonograph, a machine which enables one to see sound patterns, demonstrated that many of his theories are correct.”

Stockwell Obituary Describes Bolinger’s Talk

Robert Stockwell, on p. 107 of his obituary for Dwight, described the following:

“In the spring of 1958, just two years before he left USC permanently, Bolinger’s distinction was acknowledged by his colleagues at USC through a tradition known as The Graduate School Annual Research Lecture. This was a truly gala event, with formal dining in a great hall followed by the lecture itself. The guest of honor was permitted to invite his family and a couple of non-USC faculty colleagues; the other guests were local faculty and university dignitaries, donors, and the like. Bolinger invited William E. Bull and me; we had been working with him on a Department of Education grant to improve the methods and materials available for Spanish instruction. His lecture was about ‘Machines that talk’. It was one of my first exposures to the synthetic use of sound spectrograms to generate speech. As I noted above, he had spent most of the previous year at Haskins Laboratories, and a whole series of papers were about to appear, based on experiments performed during that year that devastated much of the conventional wisdom about stress and pitch and intonation. The lecture was designed for a lay audience. Every step was carefully prepared; there was no need to back up at any point and explain some concept which might unexpectedly be needed for the audience to follow the argument. By the end of an hour and a half of the most beautifully crafted presentation you can imagine, every one in the audience had a state-of-the-art understanding of speech synthesis. To this day I have not heard a better lecture, ever, by anyone.”

The following article appeared in the Los Angeles Times on Apr. 25, 1958: